If you go to the Boulder Farmers Market on a Saturday in the summer, you will see that agriculture is thriving in Boulder County. Where did it all start? The evolution of agriculture in the Boulder Valley began almost immediately upon its settlement by miners decades ago.

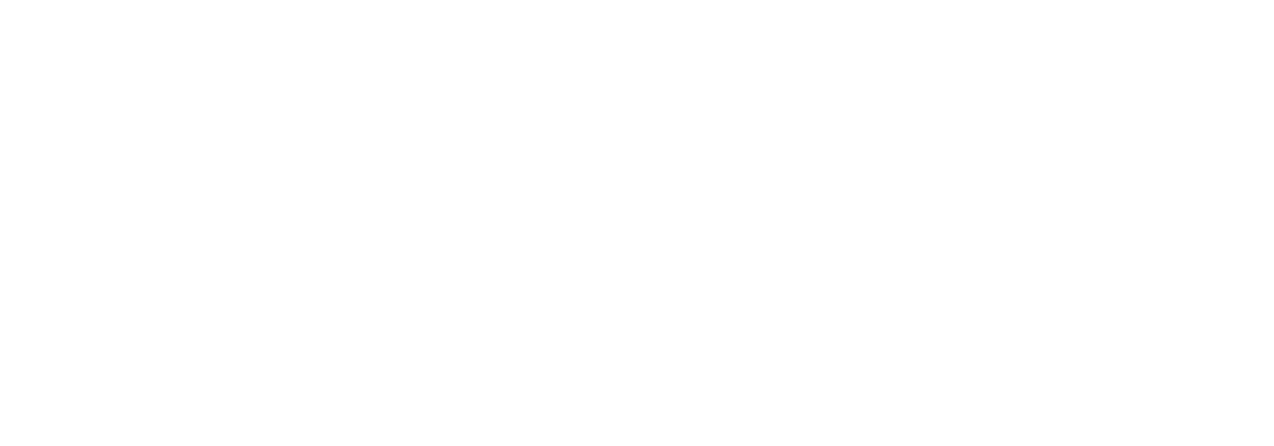

Irrigation: “A Constructed Oasis”

Early westward explorers found the plains east of the Rockies to be an arid desert unfit for cultivation. When Boulder was settled in 1858-59, the original attraction was gold mining. But miners have to eat, and farmers followed, initially growing crops near creeks. However, because sugar beets, dry beans, potatoes, and fruits need consistent water through the growing season, the farmers quickly realized that they needed a system of irrigation. By 1862, several ditches supported both farming and household water needs. Today, 28 irrigation ditches still flow through Boulder. The first ditches were simply water diverted from existing creeks, but in the 1870s, the town was piping water down from higher elevations and building reservoirs. Irrigation methods ranged from basic gravity flow into furrows to more sophisticated ditch control using headgates, spillways and lateral gates. This irrigation system is the “constructed oasis,” as water management expert Bob Crifasi has called it.

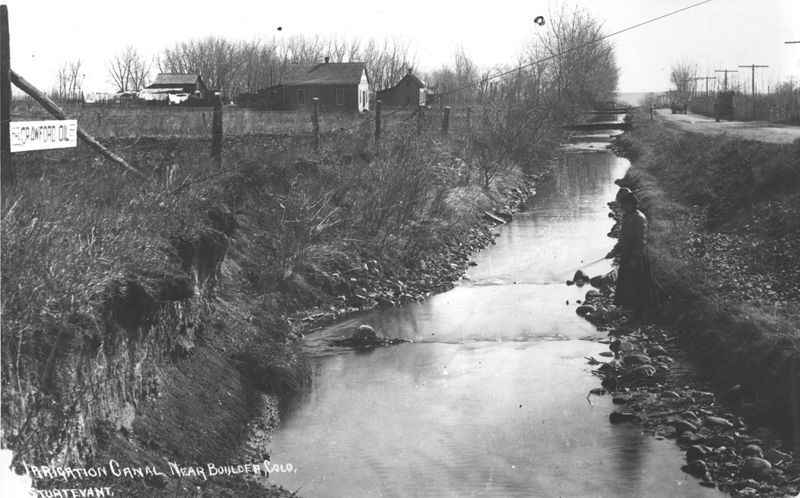

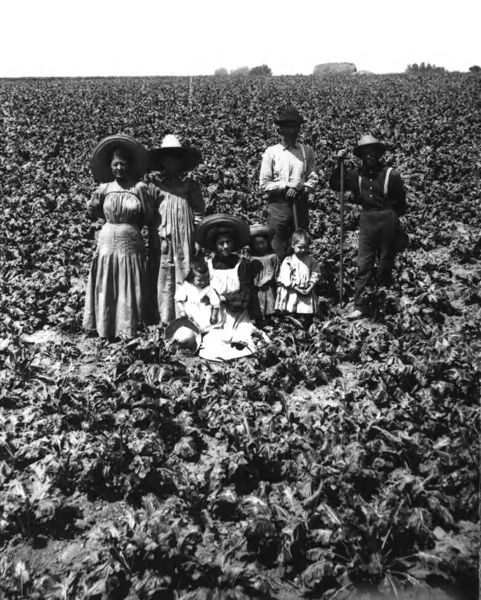

Sugar Beet Farming: A Tough Row to Hoe

The 1930 U.S. Census showed that agriculture had outpaced mining as the primary occupation of Boulder County residents. A massive spike in population growth in Colorado came around the turn of the 20th century, thanks to sugar beets. In 1888, an experimental study conducted by Colorado A&M College determined that Colorado’s soil and climate were ideal for growing sugar beets. Due to the establishment of the Great Western Sugar factory in Longmont in 1905, sugar beet farming became a mainstay of agricultural activity in the county for several decades.

Growing sugar beets required difficult and dangerous manual field labor. It was known as “stoop labor” because workers generally had to stand bent over or kneel to work the crops with knives and hoes. Many workers suffered from back and joint ailments as a result. Others had injuries resulting from “topping” work in which the above-ground leaves were cut off with a knife or machete. Sugar beet migrant workers were initially recruited from Germany and western Russia, but later, in addition to Japanese and Native American workers, the majority were Latino families. Usually, they were employed in an arrangement with an individual farmer who hired the head of a family under a contract that necessitated labor by other family members during peak stages. Great Western supplied the farmers with standard labor contracts, which established a uniform pay scale. Housing for the family was generally provided at the farm where they worked.

The expiration of the Sugar Act in 1974, along with other issues in the sugar industry, signaled the end of sugar beet farming’s heyday. Great Western, which at its height had more than 20 Colorado factories, closed most of them including the Longmont facility. However, a facility currently exists in Fort Morgan, and sugar beets are still cultivated on both private and open space land in Boulder County.

Centennial Farms

Boulder County agriculture experienced many ups and downs–from the 1890’s drought to increasing demand and prosperity during World War I, and then the devastation of the Great Depression and Dust Bowl. The state of Colorado recognizes the farms and ranches that have survived all this with its Centennial Farm program. Among other criteria, a farm or ranch must have been owned and operated by the same family continuously for at least 100 years and still be operating as a ranch or farm, as well as having at least four surviving historic structures. As of 2006, Boulder County had 22 properties designated Centennial Farms, five of which are within Boulder city limits. Due in part to open space acquisitions of agricultural properties, the traditional farm family living and working on their land has been replaced in many cases by a lease agreement with an off-site tenant. This shift may affect whether more farms are considered “Centennial Farms” in the future but won’t change Boulder County’s rich agricultural heritage.

To find out more about Boulder’s history visit our friends at the Museum of Boulder. This blog was written in partnership with Elevations Credit Union and Museum of Boulder.